Can You Trust the Apps and Sites You Use?

Let’s hope every tech company steals this idea.

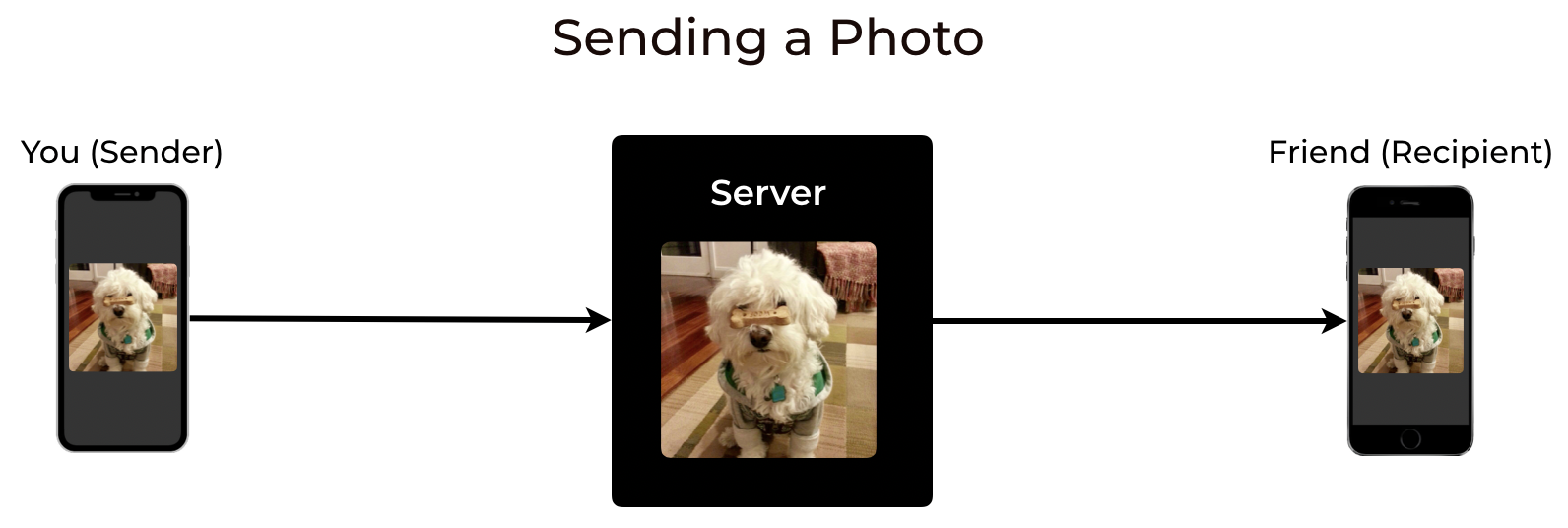

When you send a photo to someone, your messaging app actually first sends the photo to an app’s server, which then sends the photo to them:

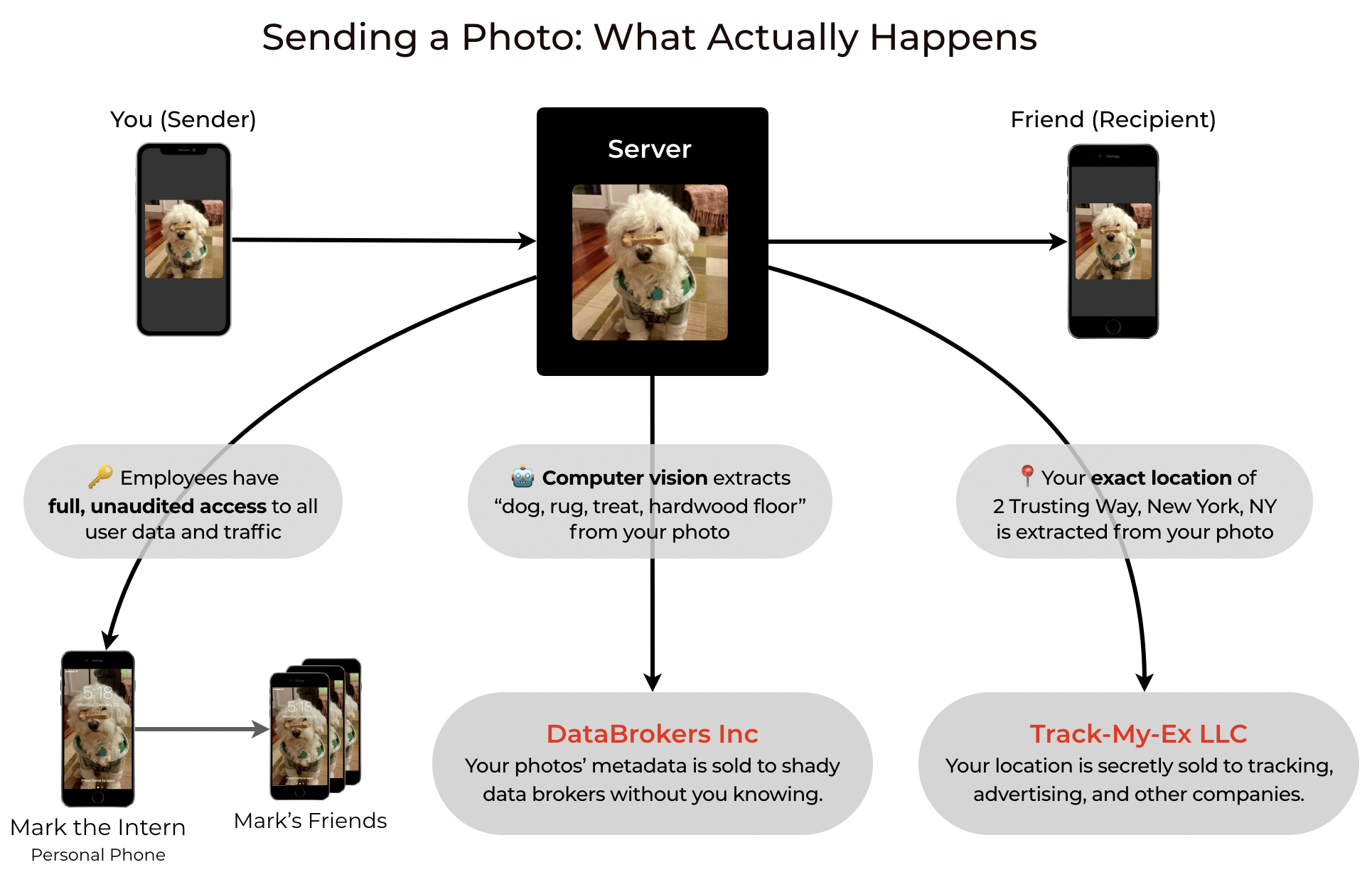

And sure, in the 90’s, this might have been what happened. But somewhere along the line, someone figured out how to profit from user data, and so now here’s what actually happens:

And that’s just sending photos. Today, you give apps access to your camera, location, microphone, contacts, browsing habits, even your medical records. After you tap “Allow” once, an app can even upload your entire photo and video library to their servers in the background while you’re sleeping.

The Internet is facilitating an insane free-for-all for our personal data, with potential consequences getting worse. Apps even exploit this data with behavioral science to squeeze every dollar or minute out of their users, when it’s clearly against the users’ best interests. Today, companies have every incentive to exploit our data for profit, and no incentive to protect our privacy.

Since we’re only going to rely more on apps over time, the critical question is:

How do you know if you can trust an app?

Trust Through Privacy Policy?

When you ask a company about protecting your data, they respond by telling you to read their Privacy Policy, which is a document they wrote (or copy-pasted) that promises they’ll protect your data.

But wait, isn’t that circular logic? I should trust that they’re protecting my data because… they have a document that says they’ll protect my data? How do I know they’re doing any of the things they claim in the Privacy Policy?

It turns out it’s impossible to know if an app company is violating their Privacy Policy (or violating privacy laws), because there’s literally nothing stopping them: they’re Privacy Policies, not Privacy Proofs. Not only that, they’re actually not legally binding, and in the rare cases when companies actually *do *get caught, the penalties are unbelievably light. And as recent government (in)action on data breaches, ISP privacy rules, and net neutrality show, often there are no penalties at all.

Privacy Polices and regulations do not create real trust, and they only serve to provide a false sense of security or privacy.

Trust Through Pricing?

It’s a common saying on the internet: “If the product is free, then you’re the product.” And while that’s sometimes true since revenue must come from somewhere, some people make the logical fallacy of thinking the inverse must also be true: “If the product is not free, then you’re not the product.”

Due to this mistake, some people use price as a criterion when choosing apps to use, by looking for apps that aren’t free and making the false assumption that non-free products will not exploit their data for profit.

Of course, it’s very possible and just as likely for a company to both charge you for an app while also profiting off of your data or having poor security. Therefore, pricing is a bad criterion for finding an app that you can trust.

Trust Through Aesthetics/Design?

Woah, those app screenshots look so sleek! And their website is so colorful and tastefully designed, with beautiful animations that you simply can’t resist. Why would an adorable cartoon bear lie to you? Is that even possible?

Well sadly, yes — cartoon characters lie all the time. Since they were created by a human and their dialogue is written by a human, an adorable cartoon bear is not less likely to exploit your personal data for profit. It might look cuter while doing it though.

The aesthetics of a website might tell you that that they spent $20 on a SquareSpace theme (or pirated it), but say nothing about how trustable an app or service is — it‘s even possible that the company skimped on data security in order to spend more on their website’s design and animations.

Trust Through Popularity?

If all your friends jumped off a digital bridge, would you? At one point, Yahoo had over three billion accounts, and in 2013, they broke the world record 🎉for biggest data breach ever, by a very long shot. Since then, there have been many more breaches of tens or hundreds of millions accounts of other companies. And these are only counting disclosed and known breaches — nobody knows what the real numbers are.

Popularity isn’t a reliable proxy of how trustworthy an app is. In fact, there are even scam apps that make it into the top charts of the App Store.

So what actually creates trust?

Apps should have to earn the trust of its users, especially when there are such strong financial incentives for companies to simply lie and abuse user data.

To earn user trust, apps should be fully transparent— the public should be able to see everything the app and its servers are doing, so that anyone can verify that there’s no negligent, dishonest, or even malicious activity. In other words: trust through transparency.

Trust Through Transparency

Full transparency means making the entire operation of an app public and verifiable, from the app code on your phone or computer, to the server code and infrastructure on the cloud, to the actions of the company’s employees, plus proof of all of that. It’s *everything *that touches your data. Everything.

If getting full and verifiable transparency from the apps we use every day seems like a radical idea, it’s because we’ve been trained for so long to expect so little from companies. We’ve been trained to upload our personal data, cross our fingers, and simply hope for the best. The truth is, if we’re giving companies our most sensitive personal information, why shouldn’t we expect them to give us proof of exactly what they’re doing with it?

A Standard For Transparency

To be clear, partial transparency is insufficient and misleading, because it still allows “bad bits” to be hidden, defeating the purpose of transparency. For example, a company hiding just a small part of their server code is still able to secretly copy all user data to unknown third parties from their servers.

So how do we know if an app is being fully transparent, versus only partially transparent or not transparent at all?

A standard for full transparency doesn’t exist today, so we’re creating one and giving it away for free.

This new standard is called Openly Operated, because full transparency requires the entire* operation* of an app to be open and verifiable. This includes making public all app source code, server code, infrastructure, and employee actions, as well as providing proof of accuracy and validity. It’s like giving the public read-only access to the app operator’s Admin console (example here).

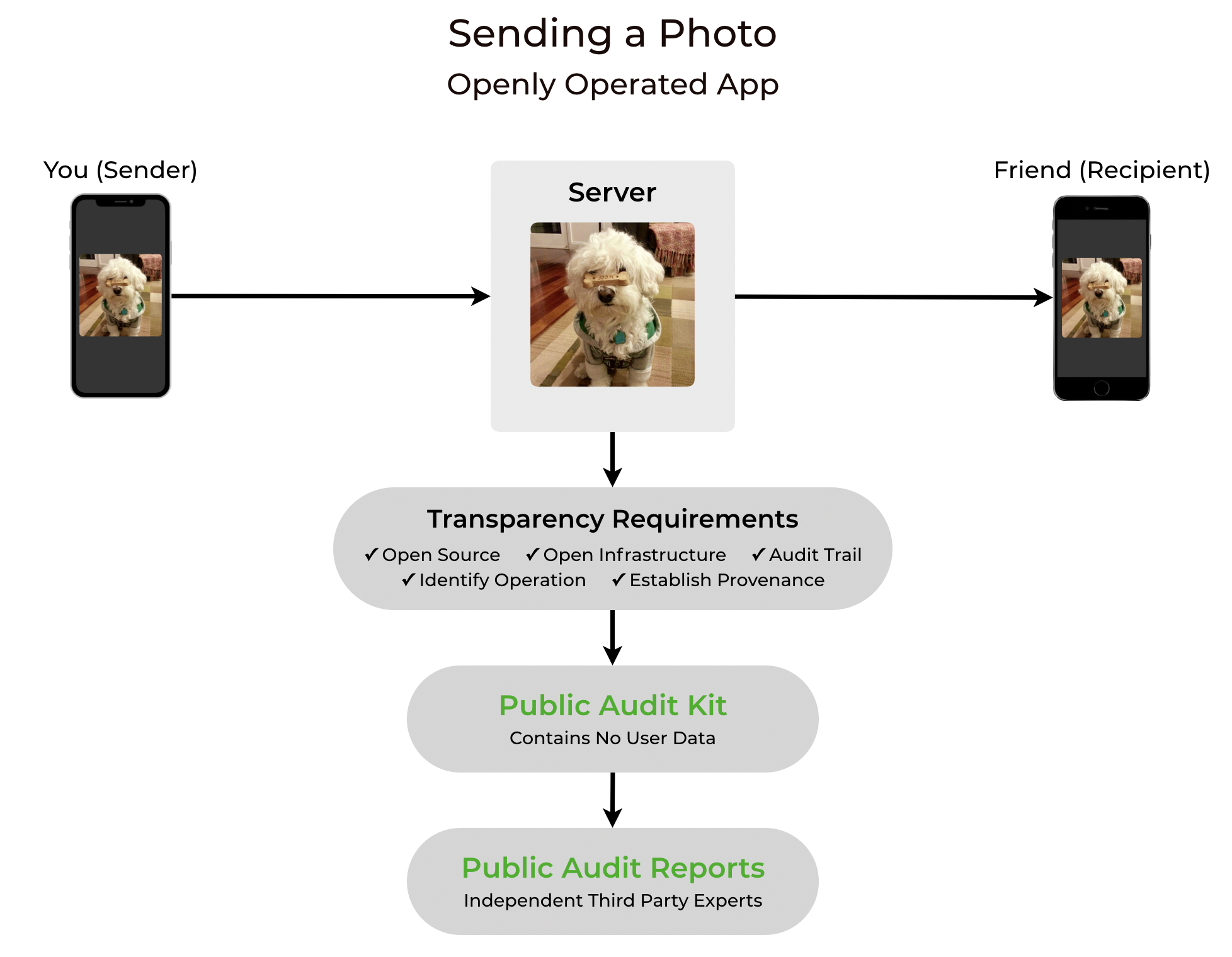

How this is different from apps today? Here’s the photo-sending example from the beginning again — except this time, the app is Openly Operated:

Unlike the earlier examples, the Openly Operated certification process forces the app to be fully and verifiably transparent, preventing the app’s operators from hiding privacy and security issues. This process, at a high level, is:

-

The app fulfills specific requirements to demonstrate full transparency, and uses direct references to source code, infrastructure, and other evidence to prove the app’s privacy or security claims.

-

Combine these requirements and proof of claims into an Openly Operated Audit Kit that anyone can publicly view and verify.

-

Get matched with independent auditors, who verify the Audit Kit to produce public Openly Operated Audit Reports, detailing their verifications and providing a summary.

This lets everyone participate in “trust through transparency”: users who are more technical can perform verifications themselves by diving into the nitty gritty details in the Audit Kit, while less tech-savvy users can read the independent Audit Reports and summaries. Openly Operated’s transparency is the opposite of the status quo, where apps simply tell users to read their totally unproven and unverifiable Privacy Policy.

Openly Operated is a free certification. Its mission is for all apps to earn trust through transparency, so all documentation is available at no cost, and companies pay nothing to license the certification. We’ve even built examples to show that Openly Operated apps are possible. These are more than proof-of-concepts — they’re in production, fully functional, and are operating at scale with real users.

Everything Should Be Openly Operated

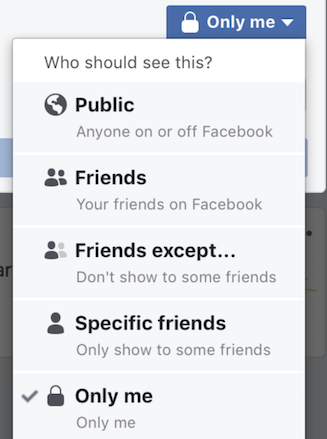

Companies have been blatantly dishonest with how they handle and secure user data for too long. Since its creation until now, Facebook has had a privacy setting for user posts labeled “Only Me”. To any regular person, “Only Me” has a simple meaning: me, and literally nobody else.

But over the last ten years, we’ve learned the hard way that Facebook has a very different definition of “Only Me”. To Facebook, “Only Me” means “Me and All Of Facebook’s Advertisers and Their Partners and Some Of Facebook’s 25,000 Employees and Some Unknown Number Of Contractors and Facebook Apps That Friends or I Have Used and Those Apps’ Employees and Anyone Those Apps Share Or Sell Data To… Maybe”.

Probably need a smaller font to fit the truth here.

Probably need a smaller font to fit the truth here.

Privacy and security scandals happen every week not because companies are evil, but because like anything else, companies operate on incentives. In a world where there’s no way to verify an app’s security or privacy claims, why should a company be honest and make less money, while their competitors are being dishonest and making more money? Current incentives give dishonest and insecure companies an edge to grow faster, compete more efficiently, spend more on marketing, and capture the most customers.

Openly Operated provides a structured way for companies to prove their privacy and security claims. Users have nothing to lose and everything to gain by demanding transparency from the apps they give their personal data to. The question shouldn’t be “Why should the apps I use be transparent?” — it should be “Why aren’t the apps I use transparent? What are they hiding?”

Learn more at OpenlyOperated.org. Whether you’re a user curious about the many benefits of transparency, an engineer building apps people can trust, or a company that wants to win customers while increasing security, Openly Operated has something to offer you.

Wouldn’t it be nice if “Only Me” really meant “Only Me”?